Niv Sekar is an illustrator, animator, and writer whose comic output consists of short but deeply emotional explorations set amidst speculative, but still familiarly mundane, settings. Her previous book was the ShortBox-published modern fairy tale Your Mother’s Fox, with an indelible road-trip narrative that likely still lingers in its readers’ minds.

Love In Space, Sekar’s latest book, is a result of the ShortBox Comics Fair, a digital-only comics event that debuts all-new works from independent artists. With a fascinating, moving premise that can basically be summed up as “Love Is Blind in space,” Love In Space is another great work put out by one of modern comics’ most innovative publishers who, because of lingering supply chain issues, has had to stop its famous box model.

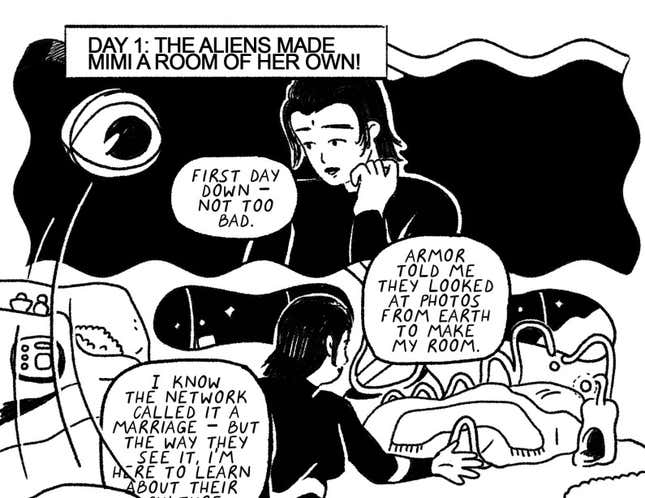

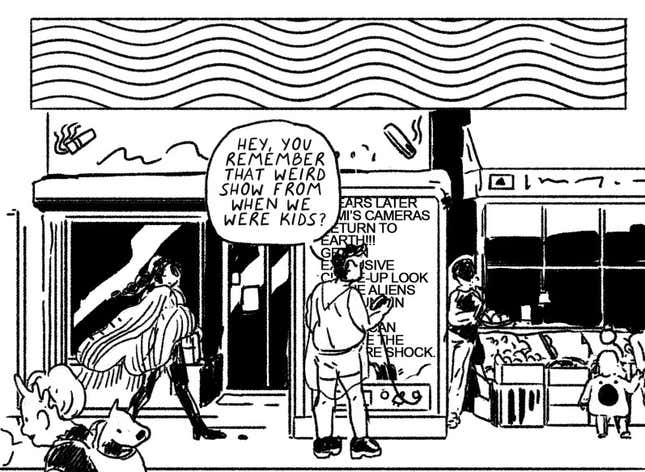

Love In Space is another entry in the realm of soulful comics that utilize the inevitable apocalypse as the backdrop for narratives that center connection. Mimi Holywater is a reality show contestant from a dying world, sent off to spend a year with an alien named Armor to see whether they form a loving bond, time dilation and all. The comic is presented as the recordings from the cameras that have returned from this year-long journey to Earth after capturing 12 months of Mim’s life. Though the world Mimi remembers is not exactly the same one that’s watching her, both Amor and Mimi are nonetheless still very much members of their respective dying civilizations.

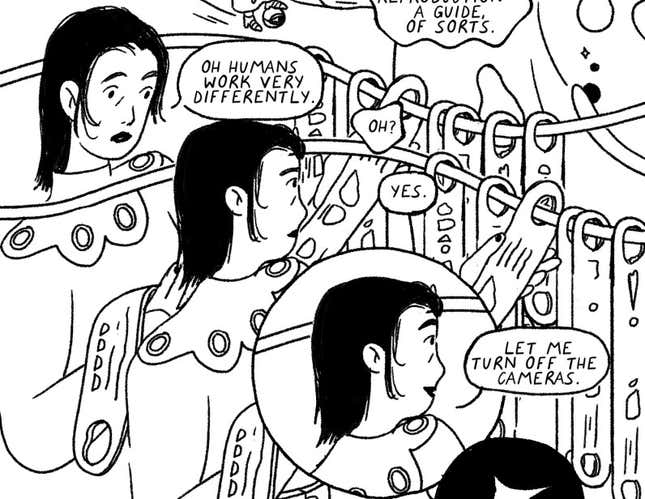

Reality television has only ever existed alongside the grim inevitability of climate change, so it’s fitting that a work is finally exploring the connection between reality TV and the end times. A single lettering distinction does the most work in evoking the aesthetics of reality programming: The font for the book’s narration, headers, and datestamps is either Roboto or Courier New, both fonts that are widespread across social media. The font is also used for the various social-media comments the Earth watchers make. Words rendered in this font tend to push the plot along, hitting the beats one expects from reality TV shows. By contrast, dialogue—most of which occurs between Armor and Mimi—is hand lettered, resulting in a touching visual intimacy between the two. (This is familiar territory for the artist: Sekar previously played with intimacy in the words of a comic by utilizing second-person narration in Your Mother’s Fox.)

There’s much about this small comic to praise, but comics aficionados will likely be most fascinated by its approach to time. There are two distinct time flows in Love In Space: the 365 days that Mimi experiences, and the years that pass for her viewers—and the reader too, technically. Most of the book focuses on time as Mimi experiences it, though the show was presumably diegetically edited in Earth time, and presented to those experiencing it as such. Cutting up time into easily digestible bits is the bread and butter of comics, and Sekar plays smartly with this technique. The panel right after the one wherein Mimi goes into a deep sleep for space travel has horizontal squiggly lines, reminiscent of static on old TVs. Readers will notice that the structure of most Love In Space pages are three wavy tiers—however much strict paneling is eschewed.

That all said, none of these deeply comic qua comic aspects of Love In Space are likely to linger with readers as much as the touching romance between Mimi and Armor—both their worlds doomed in different ways.