No one spends much time ranking Oasis albums for sport. It’s one of many ways that the most outspoken Beatles acolytes of the ’90s fail to measure up to their musical heroes: John, Paul, George, and Ringo produced such a wealth of brilliant and eclectic material, over such a short period, that debating the relative merits of their baker’s dozen of studio albums can provide a music nerd’s pastime for decades to come. True to their less expansive vision for rock ’n’ roll, Oasis poses a far simpler question: Do you prefer Definitely Maybe or (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?

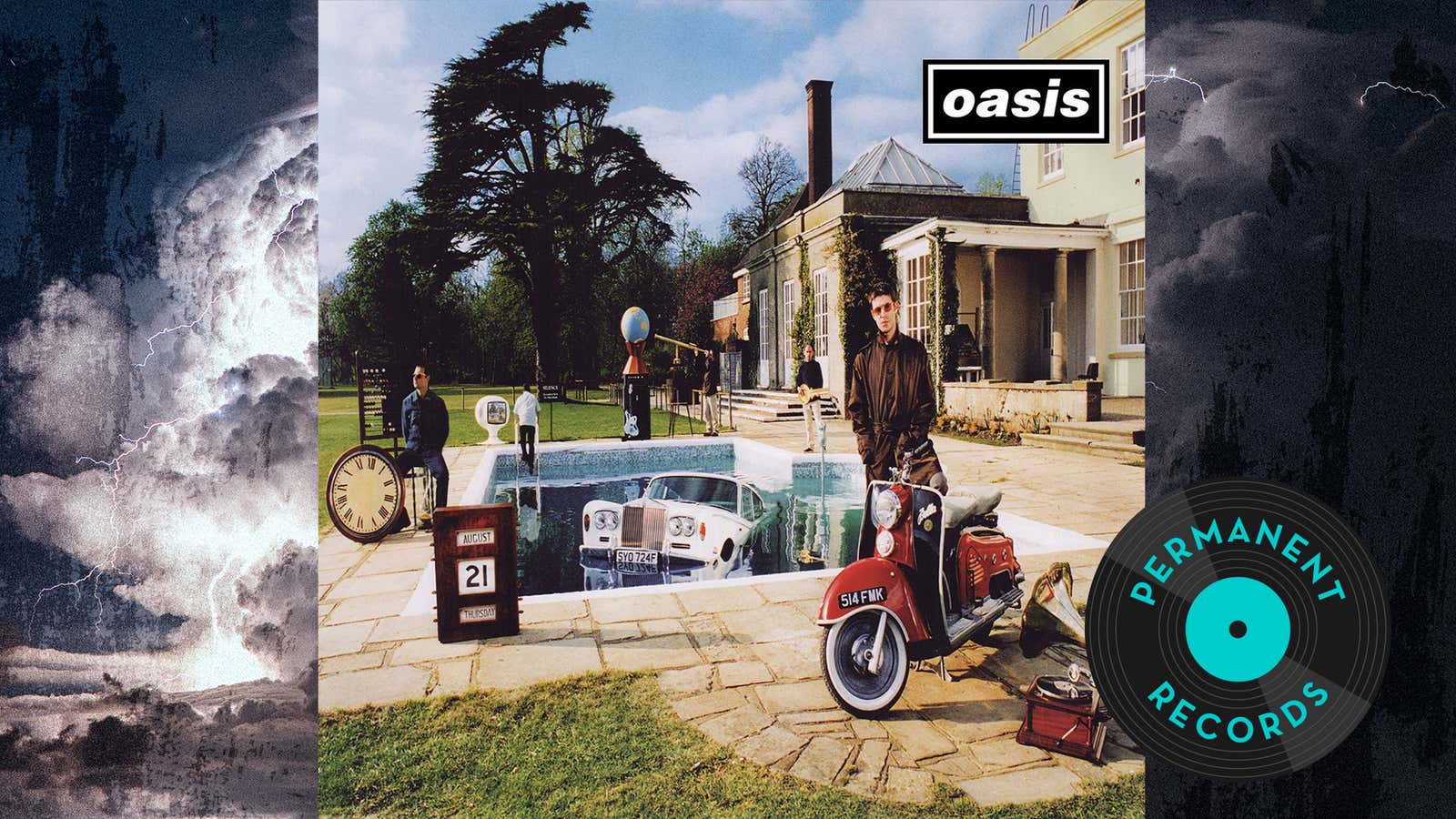

That the “best Oasis?” question would be forever limited to two records seemed less likely back in the summer of 1997, when Be Here Now, their third album, dropped. The album that essentially put a stop to Oasis as a mainstream juggernaut was also an initial commercial smash: The was the fastest-selling album in British history for nearly two decades, not eclipsed until Adele’s 25, which had a major mathematical advantage on its side. Be Here Now received plenty of positive reviews, even some raves, before—as befitting its allegedly substance-fueled creation—settling into a massive hangover. Though they went on to make four additional albums to some degree of success throughout the 2000s, Be Here Now was the last time any Oasis album was described as being as good as the first two. And a lot of the people who said so would eventually take it back.

With even greater fullness of time, though, there’s a case to be made for Be Here Now as an enduring document of Oasis, one that’s a purer expression of brothers Noel (songwriter, guitarist) and Liam (vocals, general sneering) Gallagher than the “better” albums that preceded it. Definitely Maybe and Morning Glory are superior records that happen to be by Oasis, but Be Here Now might be better at actually being an Oasis album—a dodgy distinction, to be sure.

The story that fans tend to know about Be Here Now, 25 years later, is one of cocaine-fueled excess. The album runs well over an hour, and contains just one ballad. Guitars are double-tracked, quadruple-tracked, octuple-tracked… actually, no one seems to know exactly how many guitar tracks are overdubbed onto these recordings, but “My Big Mouth” is said to contain around 30. The shortest song on Be Here Now is a two-minute instrumental reprise of a nine-and-a-half-minute song. (The second-shortest song is the four-and-a-half-minute “I Hope, I Think, I Know.”) Johnny Depp plays slide guitar on one track. Noel himself described the album as “the sound of five men in the studio, on coke, not giving a fuck.” (Johnny Depp does not appear to have been included in this count.)

To be clear, Oasis always had a penchant for a little rock ’n’ roll hubris; Definitely Maybe has plenty of songs that crest the five-minute mark. This is what’s always fuzzed the accuracy of their own comparisons to the Beatles. Listening to Be Here Now, it’s obvious that despite the multitude of winking references to the Fab Four, there is a very specific area of Beatles-ology that Noel and Liam prefer: the noise of “Helter Skelter,” the psychedelic nonsense of “I Am the Walrus” (which they used to cover in concert), and, especially, the singalong majesty of “Hey Jude.”

On the basis of Be Here Now, “Hey Jude” is the band’s second-favorite song of all time, right after “Champagne Supernova” by Oasis. Song after song reaches for a swelling grandeur somewhere between those two tracks, culminating in the endless “All Around The World,” which breaks out the “na na na”s early before lumbering through a couple of key changes.

Beneath the wall of not especially virtuosic but certainly loud guitars, there are lyrics about, uh… being in Oasis and also liking the Beatles? Again, though, these are values that are very much on display on the band’s first two albums. Their debut opens with a song called “Rock ’N’ Roll Star,” and the Gallaghers have never been shy about self-reflexive lyrics commenting on their musical aspirations—and later, stardom. They positioned themselves as the working-class blokes to the middle-class art-school kids in their Britpop rivals, Blur. (On a discography basis over the long haul, Blur beats Oasis handily. However, Blur is inarguably worse at making Oasis albums.) As Noel has noted in multiple interviews since, by the time of Be Here Now, they were now in a position where no one would dare deny them their whims. (“It’s maybe the fame,” he amusingly understates on a Be Here Now B-side.)

In this context, there are some revealing lyrical moments amid Noel’s patented anthemic nonsense. “My Big Mouth,” one of the less catchy numbers, is both swaggering and self-effacing about the Gallagher brothers’ reputation as brash fight-starters in the press: “Into my big mouth, you could fly a plane,” Liam sings, an Oasis-style humblebrag. “Don’t Go Away,” despite its string section, is one of the least overblown songs on the album. It’s also maybe Oasis’ most affecting, under-appreciated ballad—the world’s most popular band managing to sound pleading and lonely. Hell, even one of Noel’s usual catchy-sounding aphorism-via-knockoff lines, “I ain’t good-lookin, but I’m someone’s child” (paraphrased from no less than Blind Willie McTell), is an unusual sentiment for a cocksure rock band.

That line comes from the lead-off track and first single, “D’You Know What I Mean?”—a song unambiguously titled to evoke a failure to communicate. Oasis has clear coping mechanisms for this malady, and when in doubt, the lads fall back on their favorite reference points: the Beatles, and themselves. “D’You Know What I Mean?” has a line about how “the fool on the hill and I feel fine,” while “Be Here Now” (its own title derived from either something John Lennon once said, or a song by George Harrison) offers “sing a song for me, one from Let It Be.” Liam also tosses in a Bowie-style “you betcha” for good measure.

The title track doubles up with a Beatles-style reference to another Oasis song: “Your shit jokes remind me of Digsy’s,” a callback to “Digsy’s Dinner” from Definitely Maybe. Then, it’s back to “Champagne Supernova” when Liam sings about “slowly walking down the hall of fame” on “My Big Mouth.” At least it sounds like a variation on “slowly walking down the hall / faster than a cannonball”—there’s always the possibility that Noel was self-plagiarizing accidentally, rather than intentionally.

Constructing seven-minute songs that struggle to convey a deeper meaning sounds suspiciously like the height of rock-star arrogance, and has been fairly described as such in the extended Be Here Now postmortem. But there’s a strange poignancy to the album’s juxtaposition of lucidity and heedlessness. Elsewhere on “My Big Mouth,” Liam sings about “a sound so very loud that no one can hear”; whether that’s unintentional irony or genuine self-awareness, it’s the kind of touch that makes Be Here Now oddly likable in its extravagance. It’s epic-length bullshit as free-flying honesty: “This is the type of churning, wailing guitar music we want to make right now,” the band seems to be saying.

The hard comedown of the Be Here Now era cured Oasis of that desire—and, it must be said, of the Oasis sound that reached a maximalist zenith on the third album. For all the obvious touchstones—The Beatles, T. Rex, certain Bowie phases—there weren’t many bands that really imitated Oasis all that well. (Sorry, Embrace.) That includes Oasis themselves; suddenly, there was less demand for them to do their job of making Oasis albums, and they humbly obliged that downturn by taking a longer break before returning for their 2000s run, waiting out the ’90s until the Britpop scene in the U.K. and the alt-rock scene in the U.S. were diluted with second-tier latecomers.

There are highlights aplenty across the next four Oasis records—enough for at least one great album, maybe two—but despite some experiments with electronica, psychedelia, and letting Liam write, the band often sounded like they were attempting to re-bottle lightning. What’s more, they had to do so with only part of the lineup that recorded Definitely Maybe, (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?, and Be Here Now: Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs and Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan both left during the embryonic stages of album number four, Standing On The Shoulders Of Giants. The Gallaghers soldiered on with a succession of new bandmates, until Noel came to the realization that being in Oasis meant being in a band with Liam, and quit himself.

Noel has become more reflective about the Be Here Now experience, though not much less critical. Speaking in 2016 about revisiting the songs for a deluxe reissue, he discussed an attempt to pare down “My Big Mouth”: “When I got there, and I put it up, I was like, I can’t edit… this is what it is.” He later quotes a friend who describes Be Here Now as achieving a kind of fuzzy, disposable perfection: “It was just meant to be played once, on that day, high as a kite… then never to be listened to again.” That’s an extreme assessment, perhaps, but not without its appeal.

But maybe Be Here Now is still worth talking about (and listening to) because it’s an album-length document of what it was apparently like to be inside Oasis in 1997—inside the studio, inside their vision for the band, inside their heads. Making this kind of overblown rock record was not yet an exercise in nostalgia or irony; it’s a ridiculous mega-CD, released a few years before digital music would fracture everything into singles. Oasis does have some great singles, but Be Here Now offers very few of them. Most of its songs are catchy, yet none were “Wonderwall” or even “Live Forever”-sized hits, and they’re almost not worth pulling out and putting on a best-of-Oasis playlist. These are songs best enjoyed in their own big, loud company—an uncompromising, all-or-nothing affair where even the band members might now choose “nothing.” How many other bands have a whole album where their best tendencies and worst instincts are rolled together on just about every single tune?