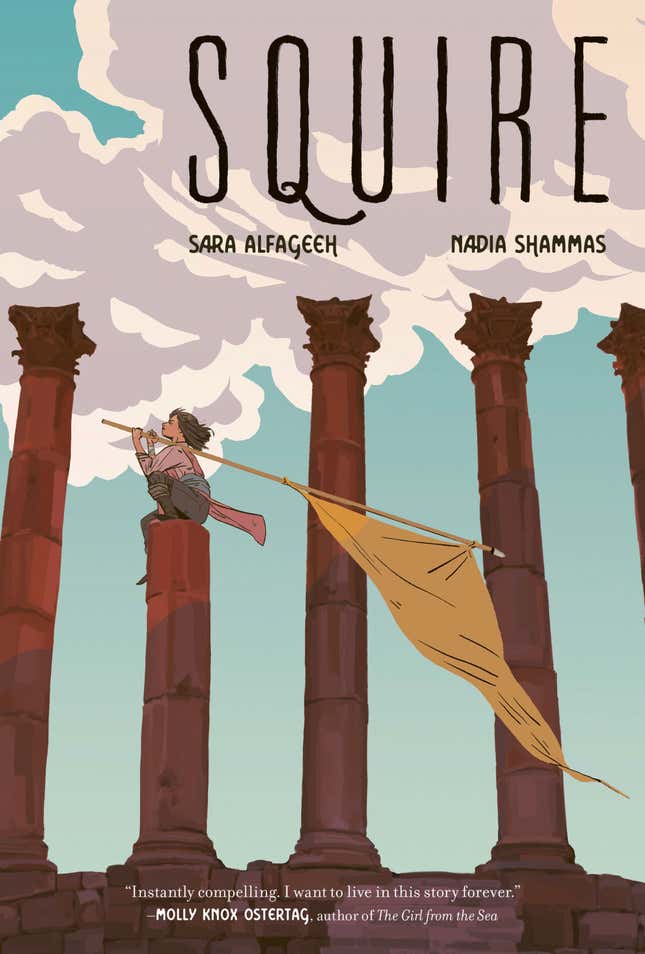

Though their names might not yet be familiar to a lot of comics readers, Nadia Shammas and Sara Alfageeh likely won’t remain that way for long. Shammas has contributed to books like Wonder Woman Black & Gold #1 and Women Of Marvel #1, and Alfageeh’s art has been featured in a Google Doodle and the TTRPG (table-top role-playing game) platform One More Multiverse, in addition to her comics work. Together, they’re an even more impressive powerhouse of talent and intention. Readers got an appetizer of their teamwork in last year’s Free Comic Book Day issue of Avatar: The Last Airbender. But new book Squire is the main course: a feast for the eyes.

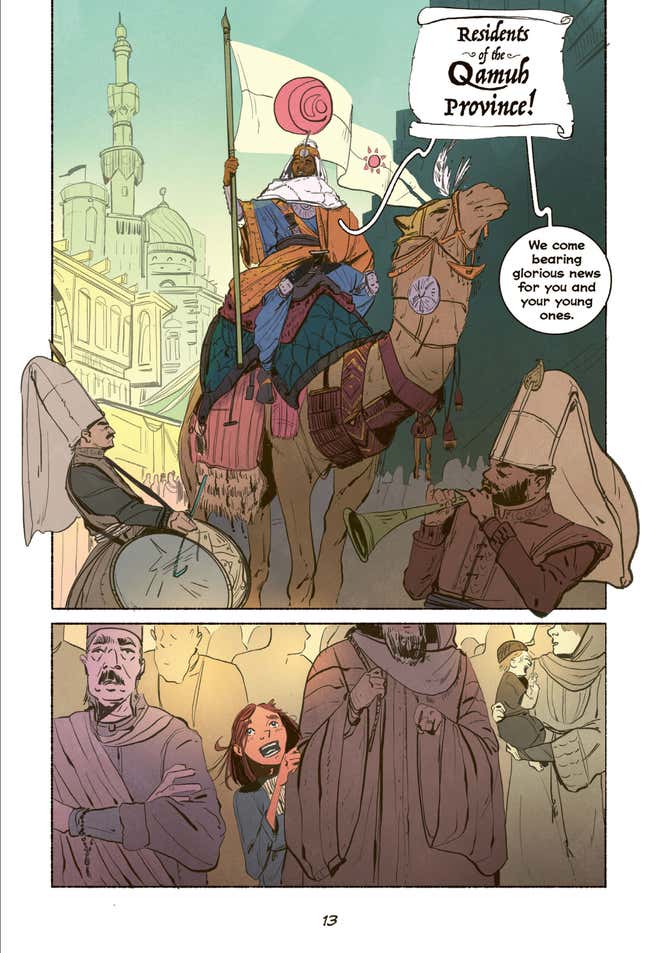

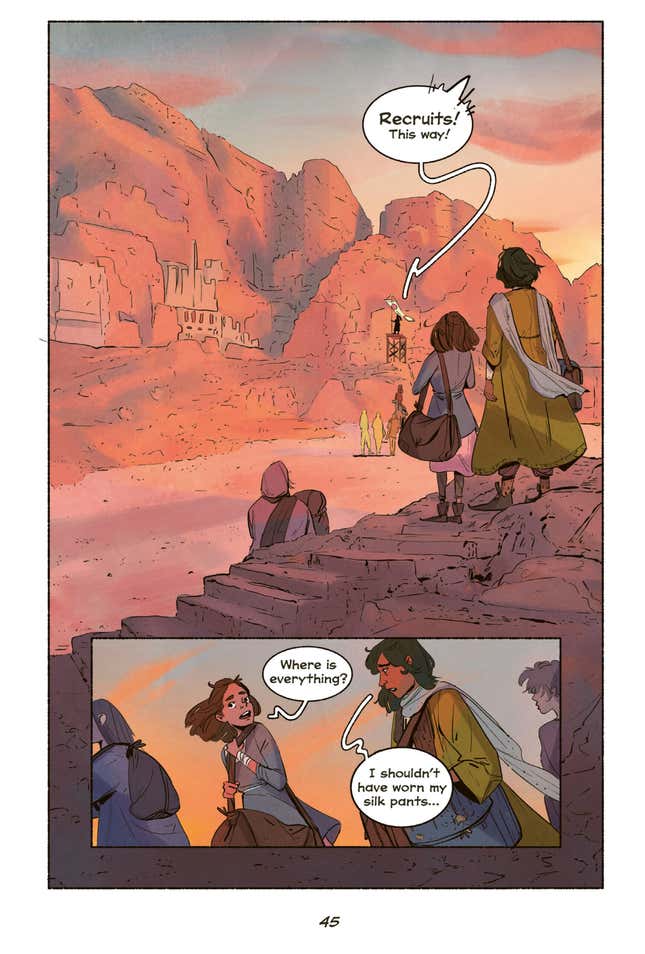

Squire is the story of Aiza, a girl chafing under not just the attention of her parents, but also the confines of a complex and layered social structure that rigidly defines her world. Presented with an opportunity to get out from underneath the poverty, food scarcity, and bigotry that have shaped her young life, she enlists in the army to train to become a squire, with the ultimate goal of becoming a knight.

Knighthood comes with money, fame, and most importantly, citizenship—a classification that has been denied to Aiza and her family, and a cornerstone of the hatred and strife that they’ve faced. As Squire unfolds, the story that Aiza and her fellow trainees have been told their whole lives about the empire they live in, and the people that live there, begins to unravel, as does Aiza’s faith in her own decisions.

This may sound familiar to lovers of young adult fantasy novels, especially those aimed at girls: There are echos of books like Tamora Pierce’s The Song Of The Lioness series, Garth Nix’s Abhorsen books, or Dianna Wynne Jones’ Dalemark Quartet. Aiza is the kind of protagonist that will leave a mark on readers, and Squire should stand the test of time better than a lot of books, thanks to careful plotting and very clear messages about assimilation, colonialism, and the way that war shapes the world. Though initially Aiza views the army as her way to combat and escape the bigotry and oppression she and her community have faced, she comes to see that this group is actually a tool to reinforce the control that a powerful few exercise over the entire empire.

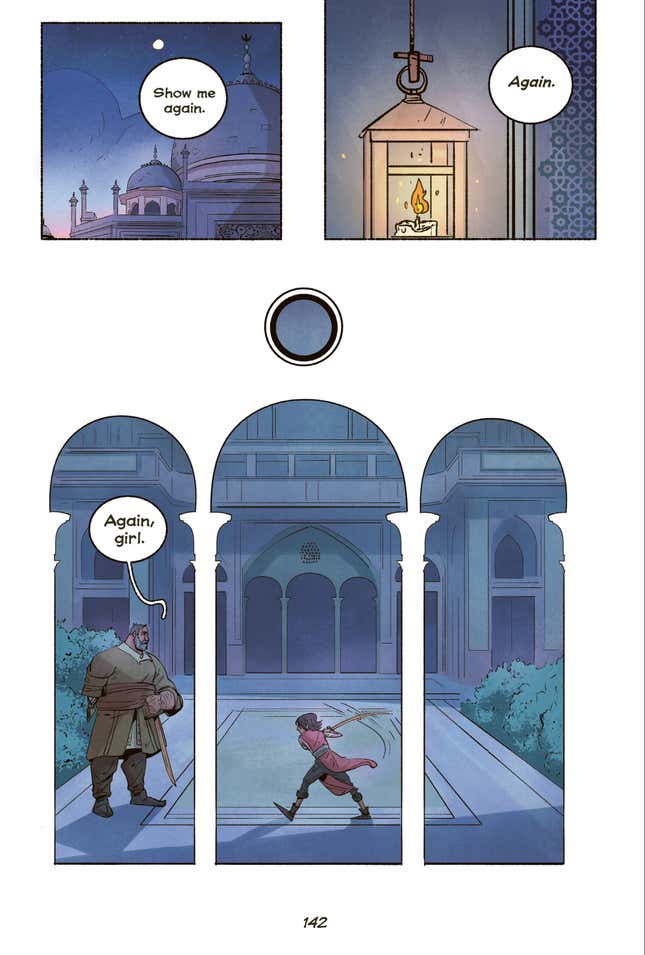

The most striking thing about Squire at first glance is how rooted it feels in a very real sense of place. The teens are drawn as such, gawky and dramatic in turns, given space for physical humor as well as carefully executed fight scenes. The art is rich with shape and color, all pointing towards different Arab cultures and identities; Alfageeh is painstakingly intentional about how characters are dressed and the weapons they wield.

But it’s the backgrounds that really sing, particularly architectural details. Other books and other artists rarely put as much weight into things like tiles and door shapes; Alfageeh breathes life into them all, understanding that everything from saddles to column shapes give the story weight and heft, making it—and the stakes—feel real.

Squire is not an exact retelling of Arab and Middle Eastern history, but it is very clearly influenced by the complicated interwoven ethnic and political powers and centuries of cultural exchange, erasure, and violence that shaped that part of the world. Alfageeh and Shammas are open about the fact that their experiences growing up as Arab-Americans who loved fantasy and comics shaped their need to make this book, and that need is to the benefit of everyone who reads this book. The cast of characters subvert expectations and defy easy explanation, offering hope but no facile solutions: Squire trusts the reader to engage in complicated ideas with understanding and generosity, to acknowledge that hard work may not pay off exactly how we want it to. This is a graceful book with a lot to offer—not the least of which is excitement over the promise of seeing what Alfageeh and Shammas do next.